AIPEI - Three years ago Mr and Ms Lee fulfilled their dream of parenthood with the help of a Thai surrogate mother.

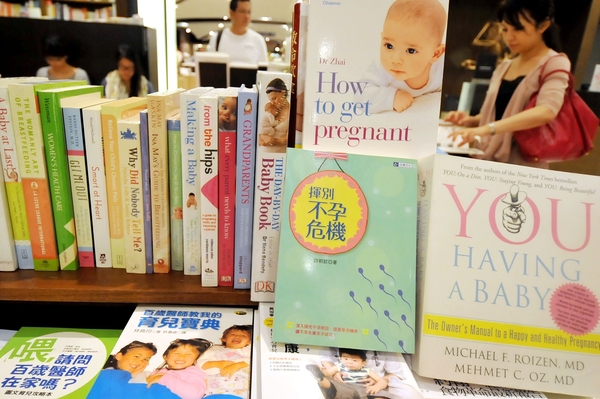

A variety of books on pregnancy and infertility are on display in a

bookstore in Taipei on June 6, 2013. Three years ago Mr and Ms Lee

fulfilled their dreams of parenthood with the help of a Thai surrogate

mother. Like many Taiwanese couples in their situation, they were forced

to seek surrogacy abroad because the procedure is illegal at home in

Taiwan. (AFP photo)

But like many Taiwanese couples in their position, they were forced

to seek surrogacy abroad because the procedure is illegal at home.

``Healthy couples cannot imagine the difficulty and pain we have been

through. We tried everything we could,'' said Mr Lee, a 40-year-old

businessman in Taipei who did not wish to give his full name.

He and his 35-year-old wife also considered adoption. ``But since

there was still a way we could have our own child, surrogacy was the

best option,'' he said.

``We envied other couples who have children and we finally felt that our lives were complete when our son was born,'' he said.

The Lees say they hired their surrogate mother in Thailand on mutually agreed terms.

``We didn't force her to become a surrogate mother, she wanted to

make money out of her own free will. I don't think it demeans her in any

way,'' Mr Lee said.

A bill to legalise altruistic surrogacy - in which a woman agrees to

carry a child for another couple through In vitro fertilisation without

financially profiting from the procedure - remains in limbo in Taiwan,

forcing couples like the Lees into the global commercial surrogacy

market.

The island is divided over the controversial and sensitive issue,

which presents a legal and ethical minefield for experts who have failed

to agree on issues such as the rights of the surrogate mother,

biological parents and the foetus.

Those who broker or make financial gains from embryo reproduction

face a possible two-year jail term, although there is no penalty for

those who pay for it, according to prosecutors.

The legality of surrogacy varies widely around the world,

particularly in Asia where commercial for-profit surrogacy services are

prohibited in many countries.

India is an exception, where the government is in the process of

passing laws to regulate a fertility industry that offers foreign

couples cheaper alternatives to options such as the US and Britain.

Altruistic surrogacy options are legally available in Australia

subject to strict screening processes. China prohibits surrogacy, while

Japan, South Korea and Thailand have no laws in place determining the

rights of participants.

Taiwan's health authorities first contemplated legalising surrogacy

about a decade ago and drafted a bill in 2005 but there has been no real

progress since then.

``In light of the demand for reproductive technology as well as some

ethical concerns from society, the bureau has been actively promoting

discussions at home and following international experiences in order to

come up with a bill that is thorough while meeting the demands of our

time,'' said Taiwan's Bureau of Health Promotion in a statement.

Opposition comes from women's rights groups, who say surrogacy

satisfies the needs of wealthy couples but overlooks the health risks

and emotional impact on surrogate mothers during and after the

pregnancy.

A surrogacy procedure can cost around US$55,000 (170,500 baht) in

Thailand to $100,000 in the United States, including medical and legal

expenses as well as payments to surrogate mothers, according to

fertility experts.

``A woman's body is not a commodity or a tool. We oppose rich people

exploiting poor women and buying them as surrogate mothers,'' said Huang

Sue-ying, chairperson of the advocacy group Taiwan Women's Link.

She urges Taiwanese couples to reconsider the traditional concept of

producing an heir and ``open up their minds'' to other possibilities

such as adopting orphans.

``Traditionally a couple would need to have a son to continue the

family line but what if a surrogate mother doesn't bear a son? I don't

think technology can resolve a cultural issue,'' she said.

Demand for infertility treatment has been on the rise in Taiwan,

which has one of the world's lowest birth rates, partly as more couples

choose to get married and have babies at an older age, doctors say.

In 2012, the average age of women who gave birth for the first time was 30.1 years old, according to the interior ministry.

Estimates of the number of Taiwanese couples seeking surrogacy range from anywhere between several hundred to tens of thousands.

Dr Liu Ji-ong, a fertility expert in Taipei, said surrogacy is the

only option for many women with underlying medical conditions.

``I think it is a question of social justice. We cannot neglect the

needs of those women who want to be mothers as they are unlikely to

speak up for themselves or take to the streets,'' he said.

Mr Lee said he only hopes that if the surrogacy bill is passed, it

recognises previous cases. Currently he can only register his son as his

child born out of wedlock, while his wife is recognised as the

``adoptive mother''.

However, he said he doubts that Taiwan will see real progress on the issue in the short term.

``It is not a major concern for Taiwanese politicians because there are just not enough votes for them,'' he said.

Asked about the chances of Taiwan passing a surrogacy bill any time soon, he said: ``I am not optimistic.''

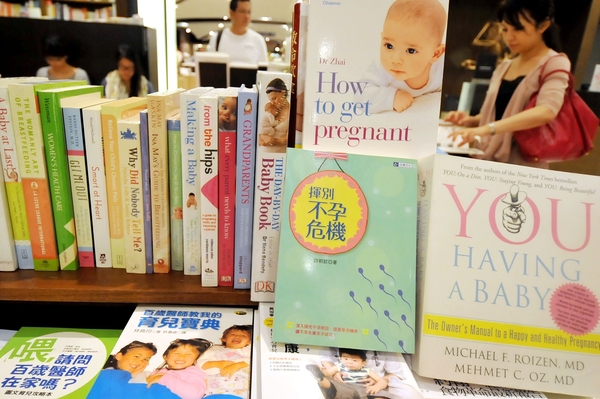

A variety of books on pregnancy and infertility are on display in a

bookstore in Taipei on June 6, 2013. Three years ago Mr and Ms Lee

fulfilled their dreams of parenthood with the help of a Thai surrogate

mother. Like many Taiwanese couples in their situation, they were forced

to seek surrogacy abroad because the procedure is illegal at home in

Taiwan. (AFP photo)

A variety of books on pregnancy and infertility are on display in a

bookstore in Taipei on June 6, 2013. Three years ago Mr and Ms Lee

fulfilled their dreams of parenthood with the help of a Thai surrogate

mother. Like many Taiwanese couples in their situation, they were forced

to seek surrogacy abroad because the procedure is illegal at home in

Taiwan. (AFP photo)